- Bevatron Demolition Plan Alarms Residents

By J. DOUGLAS ALLEN-TAYLOR, Berkeley Daily Planet, Tuesday April 5, 2005 - UC BERKELEY LAB PLAN TO DEMOLISH BEVATRON: PRESS RELEASE

COMMITTEE TO MINIMIZE TOXIC WASTE, March 2005 - BEVATRON

Mark McDonald, October 7, 2005, Berkeley Daily Planet - Bevatron Measures on Council Agenda

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet October 25, 2005 - City Landmarks Bevatron Site, Not Bevatron Building

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet August 08, 2006 - LBNL: 75 Years of Science, 75 Years of Pollution

L A Wood, Berkeley Daily Planet, August 25-27, 2006 - Community Fears Bevatron Demolition Debris

Judith Scherr, Berkeley Daily Planet July 21, 2008 - Bevatron Demolition Underway

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet June 18, 2009 - Lab Plan Describes Bevatron Demolition

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet June 25, 2009

NEWS PRINT

BEVATRON

Mark McDonald, October 7, 2005, Berkeley Daily Planet

The Berkeley Peace and Justice Commission at their September meeting passed a resolution advising the Berkeley City Council to request that Lawrence Berkeley National Lab cancel their plans to demolish the Bevatron, a defunct nuclear accelerator, or atom smasher from the 1950s, and preserve it as a historic museum and education facility. Famous for the four Nobel prizes awarded for research conducted there, the Bevatron is a winding maze of overhead circular metal pipes and machinery contained in a unique circular building with a conical roof.

This would be a wonderful opportunity for historians, students and the general public to experience one of the more interesting landmarks of atomic research in a nearby accessible setting. LBNL did apply for and was granted eligibility status for the Bevatron in the National Registry of Historic Places.

Another reason for not demolishing the Bevatron is that by leaving it intact, the significant quantities of toxic and radioactive substances locked up deeply in the walls and shielding blocks would be able to remain safely sealed with some able to decay in place, which is what is recommended by leading environmental organizations.

Like the lead paint on many of the older houses in our community, it’s better to leave non-spreading toxic substances contained and undisturbed at their site instead of spreading them around through a dusty demolition and transport process only to contaminate some other community. The toxics in their present state represent no significant danger to guests or workers.The proposed demolition will require more than a thousand trips on canvas-covered flatbed trucks through Berkeley onto the freeway and on to waste dumps as far as Nevada where the radioactive waste will be dumped. The environment impact analysis is tiered, or extended off a 1986 study that does not adequately evaluate the effects from all the truck trips on Berkeley’s air, creeks, streets or citizens.

The potential damage from this huge demolition project on the complex interwoven creek and spring system at LBNL has not included updated research and thus represents a threat to Berkeley’s creeks and emergency water sources. The $85 million allocated for the demolition could be saved and directed toward other toxic clean up projects at LBNL still waiting for funding.

LBNL has conceded that they have no plans for the demolished site so with all the potential benefits and savings to the various communities it is hoped that the Berkeley Council will agree when the resolution comes before them at their Oct. 25 council meeting. Concerned citizens can attend at 7 p.m. and sign up and if picked, can speak for up to three minutes to the council. Hopefully they will agree to petition the lab and the Department of Energy to spare this interesting landmark from the wrecking ball. Anyone who wants to help can also do so by calling or writing your councilmember.UC BERKELEY LAB PLAN TO DEMOLISH BEVATRON: PRESS RELEASE

COMMITTEE TO MINIMIZE TOXIC WASTE, March 2005

Tens of Thousands of Tons of Radioactive Debris Will be Hauled Through the Streets of Berkeley for 7 Years!The Lawrence Berkeley Lab held a scoping meeting for the public on Thursday, March 31, 2005, 6:30 p.m.-8:30 p.m., at North Berkeley Senior Center to present its plan to demolish the Bevatron (a massive particle accelerator) and Building 51. The University of California will prepare the Environmental Impact Report for this seven-year project.

The dust and debris from the tens of thousands of tons of radioactive/hazardous waste produced from the smashing of the concrete shielding blocks and metals in these facilities will contain toxic materials (which may also be radioactive) such as asbestos, mercury, lead, PCBs, chlorinated VOCs, and aromatic hydrocarbons. Some of the radioactive materials include Cobalt 60, Cesium 137 and Europium 154. Radioactive energy from Cobalt 60 can be 59 times greater in intensity than that of an ordinary X-ray.

These radioactive and hazardous wastes will be hauled by thousands of heavily loaded trucks down Hearst Ave. to Oxford, south on Oxford to University Ave. and down University to I-80. From there they will proceed to landfills in Altamont, CA, the Nevada Test-Site and Clive, Utah. The demolition is expected to continue through FY2012.

An alternative to demolition and removal would be to allow the Bevatron and its contamination to remain onsite in relative containment. Onsite containment will allow the radioactivity to decay in place and not be hauled away to other communities. This would also preserve the historic aspects of the Bevatron, as it is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places for the research in particle physics, which resulted in four Nobel prizes.

If you don't want Radioactive Asbestos Dust in your neighborhood, stores, or at bus stops, or in a truck next to your car on the street. SEND IN YOUR COMMENTS BY April 16, 2005

To: Daniel Kevin,

Environmental Planning Group

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

One Cyclotron, Road, MS 90K0198

Berkeley, California 94720………………..EXPRESS YOUR CONCERNSBevatron Measures on Council Agenda

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet October 25, 2005City Councilmembers will face a relatively light agenda when they meet tonight (Tuesday), including a proposed revision to Berkeley’s “by-right” home addition ordinance and two competing resolutions on the demolition of a UC Berkeley landmark. Competing resolutions focus on the proposed demolition of the Bevatron on the grounds of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Once the world’s most powerful particle accelerator and the source of internationally acclaimed discoveries, the facility has since been eclipsed by other larger and more specialized accelerators and has been decommissioned. At issue is whether to demolish the giant machine and the building which housed it or to preserve them and use the cleanup funds to restore contaminated ground water at the site.

Councilmembers Gordon Wozniak and Linda Maio have offered a pro-demolition resolution designed to support earlier, similar measures passed by the council, while the Peace and Justice Commission’s resolution calls for preservation and water cleanup. Since the property belongs to the U.S. Department of Energy, neither resolution would have binding effect.

City Landmarks Bevatron Site, Not Bevatron Building

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet August 08, 2006The battle over landmarking the Bevatron building ended Thursday when a city panel voted to bestow the honorific not on the structure itself but on the ground beneath.

The 5-4 decision by the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) ended an agonizing process that had lasted through months and a long series of deadlocked votes. “We’re going to landmark a site. This is starting a precedent that has never happened before,” said Commissioner Lesley Emmington, one of the dissenters. “The building seems eminently suited to landmarking to me,” said Gary Parsons.

In adopting the motion by Burton Edwards, the commission called out the details of the revolutionary discoveries made within the massive circular building, as well as the discoverers—while leaving out all mention of the structure and its unique architecture.

“This application was made by the public,” Emmington said, and called for designating the building and its historical significance.

Commissioner Carrie Olson cast the deciding vote, supporting a motion by Edwards that called on the university to memorialize the groundbreaking research carried out on what was once the world’s foremost subatomic particle accelerator.

“So we have a new landmark site,” said Chair Robert Johnson after the vote in which he opted for the Edwards motion. “It’s a complex issue.”

The commission has been wrestling with the issue since last December, when it conducted its first hearing on a proposal by LA Wood to designate the building that led to four Nobel Prizes for research that transformed the way physicists look at the way the universe works.

Officials of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory opposed landmarking from the start, declaring that the best way to commemorate the work done there was to tear it down and build new facilities for new cutting edge research.

Opinion in the scientific community was divided. The late Owen Chamberlain, the Nobel Laureate honored for his Bevatron research that discovered the anti-proton, had argued passionately for preservation before his death at the end of February.

The Bevatron building and the attached office structure totaling 126,500 square feet form part of a series of major demolitions planned at the lab. The other six large structures are in the lab’s “Old Town,” a collection of mostly wooden buildings constructed during World War II.

Demolition plans are spelled out in the lab’s 10-year site plan, released on May 20, 2005.

According to that report, demolition of the Bevatron building and the massive structure it contains will take six to seven years and cost an estimated $83 million—with work to begin before the end of the current fiscal year and ending six to seven years later.

Opposition

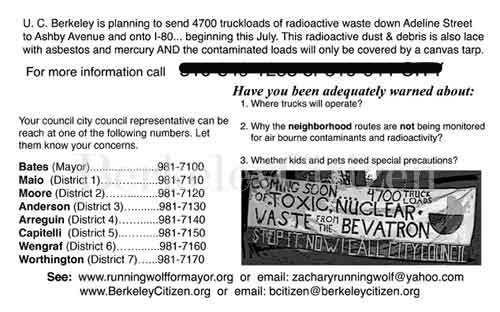

Opposition to demolition mobilized residents who fear that that the 4,700 truckloads expected to traverse city street en route to recycling facilities, landfills and hazardous waste disposal sites could spread radioactive contamination and dangerous asbestos fibers in their wake.

Critics also said they are concerned about traffic congestion, especially in light of other major construction work planned by UC Berkeley in the area of Memorial Stadium not far from the lab.

Landmarking efforts came later, and the application before the council was filed by LA Wood, who with Pamela Shivola has been spearheading opposition on public health grounds.

Many of the landmarking advocates have consistently acknowledged that their concerns were as much for public health and safety as for the preservation of a unique exemplar of Cold War architecture.

Demolition of the massive structure ranks high on the priorities of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory—and neighbors are worried that deconstruction will result in exposures to radioactive particles, asbestos fibers and other toxins.

Completed in 1953, the Bevatron was in operation until Feb. 21, 1993, when it shut down for the last time, rendered obsolete by vastly larger and more powerful accelerators.

Modern accelerators are far greater in size—with the largest almost big enough to encompass all of Berkeley within their circumferences.

But the Bevatron was unique in being the first of the world’s great accelerators, and while the accelerator itself—once the world’s largest human-made machine—has been decommissioned, much of the heavy equipment remains in place.

While Wood, Shivola and the commission minority felt the building itself should remain, the majority agreed with lab officials, who have repeatedly said the best memorial would be to replace the structure with new facilities that could generate new ground-breaking research in physics.

Even if the Berkeley Landmarks Preservation Commission had voted to landmark the building, the decision would have had little power to halt the eventual demolition of Berkeley’s last significant relic of the monumental era of government-funded Cold War science, since it is owned by the University of California, which is exempt from Berkeley law.

If Edwards has his way, the work carried out at the Bevatron will be commemorated in an exhibit, perhaps at the Lawrence Hall of Science—a suggestion repeatedly raised by lab officials.

Community Fears Bevatron Demolition Debris

Judith Scherr, Berkeley Daily Planet July 21, 2008Fearing adverse health effects related to toxic debris from dismantling the Bevatron and the associated Building 51 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and trucking the materials over several years through the streets of Berkeley, Councilmember Max Anderson is sponsoring a resolution for Tuesday’s City Council meeting—originally coauthored by recently deceased Councilmember Dona Spring—asking for a full environmental report on the impact of the demolition.

Lab spokesperson Don Medley, who did not return calls for comment, sent a copy of a letter written to the mayor and council to the Planet in which he asks the council to oppose the resolution and asserts that the demolition will be conducted safely and according to state and federal regulations.

At its 7 p.m. meeting, the City Council will also consider the reorganization of the Community Energy Services Corporation, Tom Bates Regional Sports Field maintenance and landscaping contracts, bee-friendly vegetation in parks, opposing the ban on marriage between same sex couples on the state ballot, the extension of residential parking permits to new neighborhoods, a moratorium on wireless telecommunication facilities, wording for the Landmarks Preservation Ordinance referendum title on the November ballot, an extension of the Panoramic Hill Urgency Ordinance, establishing a “sustainable energy financing district” and more.

At a 6 p.m. workshop, the council will hear a presentation on “Economic development trends in urban industrial land use,” by Karen Chapple of UC Berkeley and a talk on sustainability by Billi Romain of the Energy and Sustainable Development division of planning.

Bevatron demolition

The Bevatron is a 54-year-old defunct nuclear accelerator located at LBNL, which is owned by the Department of Energy and managed by the University of California. Hazardous materials known to be present at the facility include low-level radiation, mercury and asbestos.

“This is a city that says how green it is,” Mark McDonald, a member of the Committee to Minimize Toxic Waste (CMTW), told the Planet, arguing that trucking toxics through town is contrary to city “green” policies.

The CMTW originally called for preservation of the Bevatron building, which the city named a historic structure. Having lost that battle, the CMTW is leading the charge for a safe demolition.

In addition to calling on the lab to prepare an environmental impact statement, the resolution before council asks the lab to respond to 25 questions, including dates when the demolition is scheduled and routes through Berkeley where debris is to be trucked. The resolution also calls for assurances that the hazardous material will be tightly covered and that the shell of the Bevatron will be maintained during the demolition of the interior of the facility.

McDonald said there had been a cursory environmental review that did not take into account the 4,700 trips planned through Berkeley streets and the degree of toxicity of the material to be trucked.

Lab spokesman Medley’s letter responds to some of the issues raised in the resolution. It asserts that an environmental impact statement is not required. “The Department of Energy completed an environmental assessment on the Bevatron and Building 51 demolition, pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act,” the letter said. “Based on this assessment, the Department of Energy determined that the project does not require an environmental impact statement.”

The letter gives the project dates: between August 2008 and October 2011. And it also gives the routes for the 4,700 truck trips: Cyclotron Road to Hearst Avenue, south on Oxford Street, then west on University Avenue to I-80.

McDonald noted the lab has not revealed its future plans for the site, but the lab letter said it would be used for “in-fill” space for potential future activities.

The preferred option, other than turning the facility into a museum—which has been rejected—is to seal the facility, McDonald said. “Leave it alone and let it decay in place,” he said. “It’s not a problem as it is.”

The lab letter responds to this issue, saying that “the Berkeley Lab will dismantle and remove the Bevatron and surrounding blocks prior to the demolition of the building that contains them....”

The extent of mercury at the site is just coming to light, McDonald said, pointing to a May 20, 2008 letter to the City Council by Otto J.A. Smith, professor emeritus in the UC Berkeley Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences Department. Smith was professor in the department from 1950 to 1954, at the time the Bevatron was shipped to the university

“Every time that the system was operated with both inverters connected, one Mercury Arc Ignition tube exploded,” he wrote the council. “The public deserves to know what tests have been made on mercury liquid in floors, walls, ceiling and tests of mercury vapor in the power room at the Bevatron.”

“We don’t know what happened to all that mercury,” McDonald said, adding, “How would you feel about 4,700 truckloads with low-level radiation, mercury and asbestos going by your house?”

The lab letter underscored the safety of the transported debris. Non-hazardous materials will be transported via trucks covered with tarps and, “All hazardous and radioactive material will be packaged in accordance with regulatory requirements. For example, all hazardous and radioactive material that is in the form of dust will be fully enclosed in containers,” it said.

For a number of documents and articles on the Bevatron see: www.berkeleycitizen.org/bevatron/

For environmental assessment documents, see: www.lbl.gov/community/contruction/b51.html.

Bevatron Demolition Underway

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet June 18, 2009The unique igloo-domed Bevatron building at UC Berkeley is coming down, the closing chapter in a political battle between city activists and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL).

The structure, formally known as Building 51, once housed the 180-foot-diameter particle accelerator known as the Bevatron.

Because the structure had been the venue for experiments that led directly to four Nobel Prizes, the federal government had deemed it potentially eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places—an action that could have hampered demolition efforts.

The late UC Berkeley physicist Owen Chamberlain, who won his Nobel for discovering the antiproton in experiments using the Bevatron in 1955, had fought to preserve the structure until his death in Berkeley on Feb. 28, 2006 at the age of 85.

A group of Berkeley preservationists and citizens worried about possible radiation exposure from the transit of debris through the city had waged a losing battle to landmark the structure under city laws in an effort to block demolition.

But after months of discussion, a sharply divided city Landmarks Preservation Commission voted on Aug. 3, 2006, to landmark the site and not the building, clearing the way for demolition. Several current UC Berkeley researchers spoke in favor of demolition during the commission’s hearings.

Ben Feinberg, the last head of Bevatron operations, argued against declaring the building a landmark, telling commissioners the best monument to the history of the site would be construction of new labs equipped with the latest hardware to conduct more groundbreaking research.

Crews at the site have already stripped the structure of asbestos, commonly used in insulation materials before its cancer-causing role was acknowledged, and other interior materials have been removed and metals shipped off for recycling, according to the lab’s website on the project.

Lab spokesperson Paul Preuss said Wednesday that work continues at the site, and that a nearby traffic island had been removed to ease truck access to the parking lot at the rear of the building for eventual removal of concrete and other construction debris.

“We are presently surveying all the concrete blocks that constituted the igloo, which are currently stacked up inside the structure,” he said.

Preuss said that he expects 90 percent of the debris will not contain any traces of radioactivity above normal background levels, while the remaining 10 percent is expected to exhibit low levels of radioactivity resulting from work conducted at the site.

“That 10 percent will have to be handled in a different way,” he said, including disposal in a federally approved site.

Eventually, according to the environmental documents prepared by LBNL for the demolition, the lab expects to remove a total of 4,700 truckloads of debris, which will be hauled through city streets en route to final disposal in landfills.

The trucks now hauling material from the lab don’t come from the Bevatron, but are instead the result of work on a second project, the construction of the Seismic Upgrade Building.

“We expect to go from five trucks a day at the beginning of July to 20 a day by the end of the month,” Preuss said.

Removal of the blocks from the Bevatron building is set to begin later this month and continue through fall, according to the notice posted at the lab’s project construction updates site, www.lbl.gov/ Workplace/siteconstruction.

The Bevatron building and the attached office building total 126,500 square feet, according to the environmental impact report the university prepared as part of the demolition project.

Completed in 1953, the Bevatron—named after the billion electron volts it produced—was in operation for the next 40 years, shutting down for the final time on Feb. 21, 1993, outmoded by far larger and more powerful particle accelerators built since its inaugural run.

Lab Plan Describes Bevatron Demolition

Richard Brenneman, Berkeley Daily Planet June 25, 2009The Bevatron, at least large parts of it, will be reincarnated, in concrete form—its concrete ground back to powder and used for new construction.

Paul Preuss, spokesperson for Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, said the lab will begin moving concrete blocks from the structure in early July.

While most of the concrete will be recycled, any material containing “induced radioactivity” will be sent to the Nevada Test Site, Preuss said.

Previously nonradioactive materials can be irradiated by charged particles, such as those generated during the building’s 40-year history of high energy particle research.

Also included in the debris requiring special handling are depleted uranium blocks.

Preuss said $14.4 million of the estimated $50 million in demolition costs will come from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

“Most of the debris is the same sort of material you’ll find in any building of that age,” Preuss said.

But some resulted from the unique work done in the building.

The demolition contract was signed in Jan. 7, 2008, and work has been under way at the site, including removal of other hazardous materials including asbestos, lead, beryllium, chromium, mercury residues and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, according to a statement provided by lab officials to the Berkeley City Council last October.

The Project Waste Management Plan with specific details on disposal of all hazardous waste, including radioactive materials, was signed effective February 11 and contains detailed descriptions of all potential waste types, procedures for assessment and disposal, and requirements for staging, packaging and transport, Preuss said.

The steel-clad depleted uranium blocks were used as radiation shields against high energy particles generated by the Bevatron, according to the plan, and range in weight from 1190 pounds to 2.2 tons each.

Lead was also used as radiation shielding, and as in most structures of the same vintage, was included in the building’s paint.

Mercury was used in klystron tubes needed for some of experimental work, as well as in switches, gauges and pumps. Mercury traces remaining from at least one spill were cleaned up in the 1990s, according to the plan, but have been found in another section of the structure both in the floor and in the plumbing.

Beryllium a highly toxic metal, has been found in both solid and dust form, and chromium and copper have seeped into the wood and plastic of one of the building’s cooling towers.

Asbestos, which is known to cause mesothelioma, an invariably fatal form of lung cancer, was used as fireproofing and insulation.

The work plan calls for each form of hazardous waste to be stored in its own appropriate container, with other details spelled out in the 104-page plan document.

Radioactive wastes will be transported to the Nevada Test Site, where the Department of Energy (DOE) and its predecessor the Atomic Energy Commission conducted nuclear weapons tests.

The plan calls for hazardous and radioactive waste to be “staged,” stored in a roped off and posted area before transport, with each container appropriately labeled as to contents and their dangers, and with dikes or other separations between incompatible materials which could become volatile or otherwise more dangerous if mixed.

Preuss said all the hazardous waste will be consigned to approved toxic dumps sites.

The lab’s plans haven’t met with universal approval. A group of Berkeley activists, including Zachary RunningWolf, L A Wood, Gene Benardi, Mark Mcdonald and Carol Denney called a Tuesday evening press conference to condemn the proposal to truck the waste through the city.

Bevatron Demolition Plan Alarms Residents

By J. DOUGLAS ALLEN-TAYLOR, Berkeley Daily Planet, Tuesday April 5, 2005

Environmental activists and North Berkeley residents told Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory officials Thursday night to leave intact an unused building full of toxic and low-level nuclear wastes on its present four-acre site atop the Hayward Fault in the Berkeley hills.

The activists and neighbors said the alternative—tearing down its long-abandoned particle accelerator and carting the waste out of Berkeley in tarp-covered trucks—was unacceptable. That was the conclusion of a public scoping session held by the lab last week at the North Berkeley Senior Center as a first step in a long-in-the-planning process to demolish the Bevatron and its surrounding building.

The largest machine in the world at the time of its construction in 1954, the 180-foot diameter, 11,000-ton Bevatron was used for the next 40 years for atomic and subatomic experiments and discoveries. Use of the Bevatron ended in 1993, and LBNL officials say they have been trying, unsuccessfully, to get federal money for the demolition project. Terry Powell, LBNL community relations officer, said that Bevatron demolition money was recently released by the Department of Energy and placed in this year’s department budget.

LBNL literature says that it no longer has any use for the building or the accelerator itself, and says that because of “the significant contributions in the fields of particle and nuclear physics that were made there,” the building is eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.Under California law, the LBNL has the authority to approve the demolition project itself, but must first complete an environmental impact report (EIR) after giving the public the chance to give information, raise questions, and suggest alternatives. Last week’s scoping session was the first in that series of mandated public input processes.

Margaret Goglia, Project Manager for the Bevatron demolition, said Thursday night that the accelerator and its surrounding building contain such toxic wastes as asbestos, PCBs, mercury, lead, and machine oil, as well as low level radioactive waste, which she called “low even for this category.” She said the lab would “address the specific level of radioactive waste in detail in the EIR.”. If the demolition project is approved, Goglia said the lab plans to remove several tons of concrete blocking surrounding the accelerator, dismantle the Bevatron, demolish the surrounding building, remove layers of soil from the site, and re-soil with fresh earth.

Goglia said that “a lot of the demolition work will taken place indoors,” inside Building 51 that houses the accelerator, and that the waste and soil would be removed in “several thousand one-way truck trips” on a route from Hearst to Oxford to University Avenue and then to Interstate 880. Goglia said this route was “preferred by the City of Berkeley.”

She also said that the demolition project would operate with 50 employees at its peak, far fewer for most of its duration. The project is scheduled to last between four and six years.

While Goglia said that the lab has no new plans for building on the site, Community Relations Officer Powell said, following the meeting, that this does not necessarily mean there won’t be such plans in the future. “We’re moving forward now because we have the money from DOE and we feel the site needs to be demolished,” Powell said.

But a string of community speakers told LBNL officials Thursday that leaving the Bevatron intact was preferable to demolition. Jim Cunningham, a North Berkeley resident who said he has taught at the university, said that a further discussion was needed “on the alternatives of demolition versus allowing the radioactive material to decay in place." Cunningham also said he wanted verification of the level of the radioactive waste on the site to be done by “someone other than lab officials.”

Mark McDonald, a member of the Berkeley-based Committee To Minimize Toxic Waste, said he was “concerned about the airborne contaminants” that would be released during the demolition. “LBNL should be on the cutting edge on demolition and disposal of these types of structures,” he said, “but they’re still doing this in the same old sloppy way.”

A leaflet put out by the Toxic Waste Committee prior to the scoping session criticized the demolition, stating that “an alternative to demolition and removal would be to allow the Bevatron and its containment to remain onsite in relative containment.” The leaflet called on residents to express their concerns to the LBNL “if you don’t want Radioactive Asbestos Dust in your neighborhood, stores, or at bus stops, or in a truck next to your car on the street.”

Berkeley resident L A Wood criticized the lab for moving the Bevatron demolition ahead of its long range development plans, suggesting that “maybe it’s being rushed ahead to duck” the added scrutiny called for in a formal LRDP. “Maybe the Bevatron should be preserved and made a shrine to the 1950s when the lab put these things in place in our community, with no community involvement, because they could,” Wood said.

Speakers suggested various measures should the demolition be approved, such as, “leave the site fallow after demolition so it can heal itself,” use an alternate route for trucks up Grizzly Peak to Highway 24 rather than going through the heart of the city, restore the network of creeks presently running under the structures in culverts, hire an independent agency to supervise the cleanup, and organize a field trip so that residents and activists can view the Bevatron site itself while the EIR process is going forward.

LBNL officials said public comment on the project would be accepted through April 16, and all questions raised would be addressed in the draft EIR, which will then be presented to the public. Documents concerning the proposed demolition have been placed on the LBNL’s website at www.lbl.gov/Community/env-rev-docs.html.

All Rights Reserved