Field of Bad Dreams

City of Berkeley Soccer Fields

Field of Bad Dreams: In its rush to create sports facilities at Harrison Park, Berkeley overlooked nasty environmental realities. It should have known better.

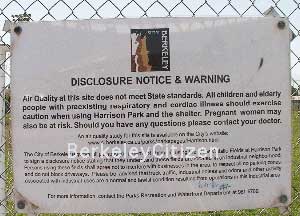

John Geluardi, East Bay Express, September 4, 2002As the fall season begins later this week, hundreds of pint-sized members of the Albany/Berkeley Soccer Club will flock to two recently built soccer fields at Harrison Park in west Berkeley. But before they hit the field in their brightly colored jerseys, they'll have to file past a grim reminder of urban living: A three-foot-square sign, posted by the city at the park's entrance warns players and their parents that the air quality at the field "occasionally does not meet state standards," and that high levels of airborne particulate matter could have an "adverse health impact" on children with respiratory problems such as asthma and bronchitis.

The warnings are the result of an ongoing $40,000 air-pollution study that began at the field just more than a year ago. The results to date are not pretty: Pollution levels at the 5.6-acre park are twice as bad as those measured by the Bay Area Air Quality Management District in downtown San Jose, and three times as bad as in downtown San Francisco, according to Nabil Al-Hadithy, Berkeley's hazardous materials supervisor. Playing soccer on the site, in other words, is like playing in heavy traffic.

Harrison Park has proven a dubious enterprise, at best, for a city that prides itself on environmental awareness. It could be argued, in fact, that city officials acted less than diligently when they bought the land from UC Berkeley two years ago as the future site of twin soccer fields and an 18,000-square-foot skate park. Now the city is considering a bid to build the Ursula Sherman Village, a multimillion-dollar, family-oriented homeless facility that will house up to 132 people, many of them children, at the site. If approved by the Zoning Adjustments Board, this long-term housing facility will be incorporated with Harrison House, a nightly shelter that has been on the site since 1975.

What makes the site controversial? For one, the park sits at Fifth and Harrison streets in the heart of an industrial district; Interstate 80, with its diesel-truck traffic, is close by, as are the city's Solid Waste Transfer Station, Pacific Steel Casting, Berkeley Forge and Tool, and other significant contributors to air and ground pollution.

Indeed, there was many a red face on the city council and in at least three city departments when the wheel-loaders digging out the skate bowls struck groundwater laden with chromium 6, the notorious carcinogen that made Erin Brockovich a household name and helped win Julia Roberts an Oscar for Best Actress.

But this was no movie. The subsequent cleanup and redesign cost Berkeley an estimated $300,000 and delayed the project for more than a year. (The skateboarding facility is scheduled to finally celebrate its grand opening on September 15.)

Faces around City Hall became redder still when it came to light that the city's own Toxic Management Division had known for a decade that a plume of chromium 6 from a nearby engraving shop was lurking nine feet below the surface, just thirty feet south of the proposed skatepark. "Full information is always better, and, in retrospect, sufficient information did not get to everybody in the proper time," says assistant city attorney Zach Cowan, who helped fashion the purchase agreement with the university. "There wasn't bad communication; there was no communication."

The city's lapses, however, went beyond the poor interdepartmental dialogue. During the rezoning process, which began in 1998, and also the city's negotiations with Cal in 2000, the city attorney's office failed to order a "phase one" environmental study. While phase ones aren't mandatory, they have been the standard in land and commercial real-estate transactions since the 1980s. Any bank involved in such a land deal would have required one, but no bank participated in this case: The city bought the land directly from the university -- "as is," one might say.

There was yet another oversight: The city's Parks, Recreation, and Waterfront Department neglected to order a California Environmental Quality Act survey of the skatepark site -- another standard, though not mandatory, study -- before excavating for the concrete bowls. While Berkeley did conduct other environmental tests on the site that showed acceptable risks, phase one and CEQA studies are project-specific and would have raised red flags, says L A Wood, a member of the city's Community Environmental Advisory Commission.

How did the oversights occur? When it comes right down to it, say critics of the Harrison Park development, the city got railroaded: A well-organized and politically potent lobby of soccer parents pressured the nine-member city council to rush into the $4 million land deal without first addressing serious environmental questions.

Diane Woolley, a former councilwoman who represented District 5 throughout the process, says the pressure to approve the project was "immense." Soccer parents, she says, represent a large voting bloc in Berkeley, and the majority of the council was afraid to ask hard questions about environmental safety. Only she and councilman Kriss Worthington voted against the rezoning and purchase.

The parents, led by Doug Fielding, president of the nonprofit Association of Sports Fields Users, didn't hesitate to use their political clout, Woolley says. "Fielding was heavy-handed, overbearing, single-minded, and shortsighted during the entire process," she says. "It was understood by the council members that this project was to be approved quickly and questions about health hazards were swept away in the rush."

While assistant city attorney Cowan admits there may have been missteps by his office, he says they were unrelated to pressure from soccer parents or even the council. But Wood, a city-council candidate who was largely responsible for forcing the city to conduct the current air study, says council members had to suspect there were environmental problems with the property. They simply didn't want to look too closely. "The soccer parents rode over city process like a runaway train," Wood says.

Talk to the parents and you'll hear a different story, perhaps surprisingly so. It is their children, after all, who will be using the site. This difference in perspective stems from the fact that Berkeley is sorely lacking in open spaces for recreation. Harrison now hosts two of six soccer fields that are used to their full capacity by the thousand-member local soccer club.

Despite the chromium-6 fiasco and the discouraging air study results, the majority of soccer parents and homeless advocates appear undaunted -- indeed, the soccer club adds members with every season, according to its organizers. Living in a built-up urban environment, they say, entails certain compromises. The parents argue that the benefits of organized sports are evident in the health and attitudes of their children, while the health hazard posed by exposing their children to dirty air for a few hours a week during soccer season are uncertain.

Fred Hetzel, a member of the soccer club's board of directors, says his two children will continue to play on the site. Hetzel says he's spoken with the air district and is confident that playing soccer a few hours per week isn't dangerous. "If parents saw their children wheezing and keeling over on the field, of course they would be worried," says Doug Fielding. "Instead parents see their kids coming home happy, red-faced, and exhausted, and that's what you want as a parent."

Homeless advocates take a similar position: boona cheema, executive director of Building Opportunities for Self Sufficiency, the nonprofit behind the Sherman Village project, says she'd be happy to build it in Tilden Park where the views are great and the air is fresh, but she doesn't expect that to happen anytime soon. "What do you think the answer is going to be when you ask a homeless mother with two kids if she would rather live on the streets or in safe, warm housing in west Berkeley?" she asks.

Warm, perhaps, but how safe? The air study shows that levels of a dangerous air pollutant known as particulate matter 10, or PM10, exceeds state standards an average of eight times a month. While the levels are measured in 24-hour averages, particulate pollution appears to peak between 1 p.m. and 3 p.m. -- coinciding with weekend soccer games. But exactly how the high PM10 levels may affect the health of young soccer players who pant up and down the field two to six hours a week, or that of the families who may soon live on the site, is hard to pin down.

State scientific and regulatory agencies including the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment and the Bay Area Air Quality Management District agree that children with respiratory conditions such as asthma and bronchitis should be closely monitored if they are going to participate in sports or live in housing at the site. But, they say, the risk to healthy children may be minimal.

"There may be a small increase in risk of respiratory symptoms in healthy children, given the data I've looked at," says Michael Lipsett, a public health physician with the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, after examining one month's air pollution data from the site. "What that would mean to the average individual is hard to tell."

Lipsett agrees with Fielding that soccer parents must weigh the benefits of playing organized sports at Harrison Park against the potential hazard of what he described as a common air-quality condition in the state's urban areas.

But it is also true that PM10 is particularly nasty. Associated with urban automobile exhaust and industrial activity, the particles consist of metals, soot, soil, dust, and liquids. They are about ten microns in diameter, an ideal size for inhalation. "PM10 is among the most harmful of all air pollutants. When inhaled, the tiny particles evade the respiratory system's natural defenses and lodge deep in the lungs. Health problems begin as the body reacts to these foreign particles," states the air district's Web site. "PM10 can increase the number and severity of asthma attacks, cause or aggravate bronchitis and other lung diseases, and reduce the body's ability to fight infections."

Lipsett's own agency was mandated in 1999 by the Children's Environmental Protection Act to review state standards for PM 10 to assure they adequately protected "the public, including infants and children, with an adequate margin of safety."

As a result of that review, the California Air Resources Board strengthened the annual standard for PM10 from thirty micrograms per cubic meter to twenty; the new standards are expected to go into effect early next year. Standards for the 24-hour average, the measurement used by the Harrison Park air study, will stay the same. The air at the Harrison site, however, exceeds limits set by both the annual and 24-hour standards.

Despite the troubling environmental issues, Parks, Recreation, and Waterfront Director Lisa Caronna is still a Harrison Park booster. "Knowing what is known about the property now, I would still support this project," she says. "This project is a winner for the residents of Berkeley."

Given her title, Caronna might be expected to say as much. But in such disputes, unlike soccer games, the winners and losers are rarely so clearly defined. For a nuance view, talk to that young midfielder who plays soccer despite her asthma, or the homeless mom with nowhere else to take her kids. While the long-term effect of building city sports fields and transitional housing amid industrial and highway pollution are yet to be determined, it seems clear that what the city has produced is far from an out-and-out win. Sometimes, when all options are considered, the rival players have little choice but to be satisfied with a tie.

Berkeley Citizen © 2003-2020

All Rights Reserved

All Rights Reserved